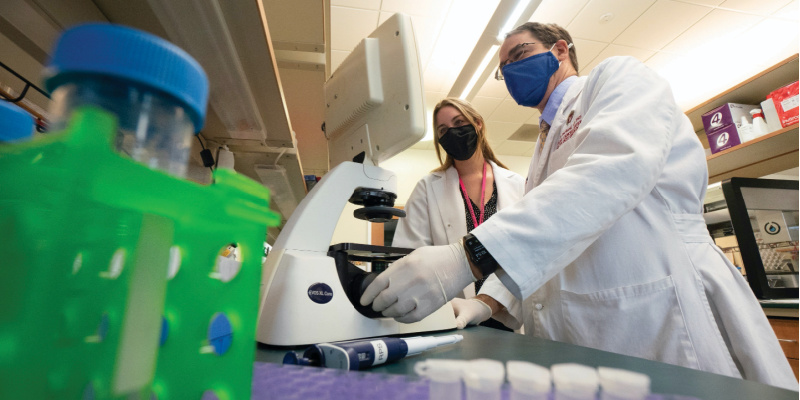

By Shelby Rowe Moyer | Photos courtesy of UW Health

Elizabeth Pronold joked it was the “Dark Ages” when she was first diagnosed with breast cancer.

She was 30 years old in July of 1979 when she found what felt like a lump in her breast. Pronold had graduated from nursing school just a couple years prior, so she knew this mass could be something. But, breast cancer? At her age, she didn’t think that was likely.

When she was diagnosed with ductal and lobular breast cancer, the medical field was just beginning to expand treatment options and some of the technology certainly wasn’t as good as it is now, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

In the past 40 years, much has changed. Breast cancer used to be more deadly, but as diversified and targeted treatments emerged, positive outcomes for patients have increased. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the number of women who have died from breast cancer decreased 40% between 1989 and 2007.

UW Health oncologist Dr. Mark Burkard, who specializes in breast cancer and is a professor at the University of Wisconsin- Madison, has spent the past several years researching what he hopes will shed more light on an incurable form of cancer, metastatic breast cancer, with his study titled “UW’s Outliers Study of Extreme Long-Term Survivors with Metastatic Cancer.”

Metastatic breast cancer is breast cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, like bones, lungs, liver, brain or other organs. It only emerges in 30% of breast cancer survivors. Those that develop it, however, only have a five-year survival rate of about 27%. The survival rate beyond five years is even more dismal.

Pronold is among the unlucky 30% of those diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. More importantly, though, she’s among the few who is living with it. A 2017 biopsy of a lesion on her right temple revealed that her breast cancer had metastasized to her skin, and scans also showed the cancer was in her bones and lymph nodes.

After learning about and participating in Burkard’s study, Pronold thinks she likely had metastatic disease long before her 2017 diagnosis. She hypothesizes that it may have been so slow growing that it allowed her to live with it for decades. Today, she’s taking an oral medication that keeps the cancer at bay, allowing her to live a happy and healthy life.

But what’s different about Pronold is that she’s considered an “extreme long-term survivor?” That’s what Burkard hopes to figure out.

Burkard began the Outliers study around 2016, after he met Peg Geisler, a Wisconsin woman who was diagnosed with metastatic disease in the early ’80s.

“She beat those five-year survival statistics,” Burkard says. “Then she beat the even-worse 10-year survival statistics. Then she beat the 20-year survival statistics, and she even beat the 30-year survival statistics. So, I knew right away that her story was incredibly unusual. I guess the question was, ‘Why?’”

Initially, the Outliers study only included patients who had been treated at UW, but with the help of grants and cancer organizations, Burkard was eventually able to collect information from more than 1,000 people around the world who have metastatic disease.

The survey is still open for metastatic survivors to take online, but Burkard’s team has already released some preliminary results from participants’ information, which revealed the most common metastasis site was bone, and that only about 100 of metastatic survivors have lived with the disease for 10 or more years. It also showed that lifestyle impacts, like exercise, don’t seem to correlate with survival rates, which wasn’t surprising to Burkard, but was a little disappointing.

“I would love to be able to have something to empower people to control their destiny, but that’s not what we saw,” he says.

More recently, Burkard narrowed down 50 participants who are the longest survivors of metastatic disease and collected tumor samples (if they were still available) and saliva samples for genomic testing. The analysis Burkard is doing is threefold: looking at lifestyle (diet, exercise, sleep patterns), cancer treatments and genetics.

Burkard says two groups have already emerged in his preliminary analysis: exceptional responders (those who responded very well to their treatments) and exceptional survivors (those who seem to have such a slow-growing cancer that, even if they aren’t being treated, they seem to have a strong survival rate).

For the exceptional survivors — like Geisler who isn’t currently undergoing cancer treatment — he hopes the genomic testing will reveal some correlations. He has some theories about why some may be exceptional survivors, which could include the immune system.

“It’s possible that people like Peg [Geisler] live long because their immune system has successfully detected the cancer as foreign and has been able to suppress it [because] the immune system is destroying cancer cells,” he says.

The study has a long and challenging road ahead, Burkard says. He’s hypothesizing that the participants’ information will fall into several subgroups, and for some, he may have no explanation at all.

Though the Outliers study is about four years in the making, Burkard says this is just the beginning. He hopes to analyze more information and increase the demographics of his participants. Currently, he has little data from men, and those that are Hispanic or Black.

Pronold keeps an eye on the study’s webpage, which is updated every once in a while with new information. Only a handful of people in the study were first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1979 like her, so she’s interested in their results as well.

For Pronold, the study’s outcome isn’t really about her survival — she hopes the study could reveal genomic markers that can be identified and tested in other people.

“I’m hoping that if there’s something from my parents — or that I could pass on to my children,” she says, pausing. “I have two biological boys. I think it would be great if there were markers to watch for. I think that’s really my hope.”

This article was originally published in BRAVA’s September/October 2020 issue and was accurate at the time of publishing; however, some information may have changed. We recommend verifying information ahead of time if you plan on visiting or patronizing any businesses.