Black women leading the way toward lower infant mortality rates

By Julia Richards | Photographed by Hillary Schave

Tia Murray knows firsthand the power of community in supporting a young first-time mom. She had her first baby when she was 18, while her mother was working at the Harambee Center, a collaboration of social service providers that provided a one-stop-shop for families until it lost funding and closed in 2010. “When I was a young teen mom I benefited from the community baby showers there, received education, learned about their breastfeeding support groups for women of color and went on to breastfeed my first baby for two years,” says Murray.

The center, whose name comes from the Swahili term meaning “pull together,” was a model for addressing the many social factors that affect health outcomes. It may have played a role in reducing the black infant mortality rate in the state in the mid-2000s, says Murray, who speaks in a soft, but firm voice.

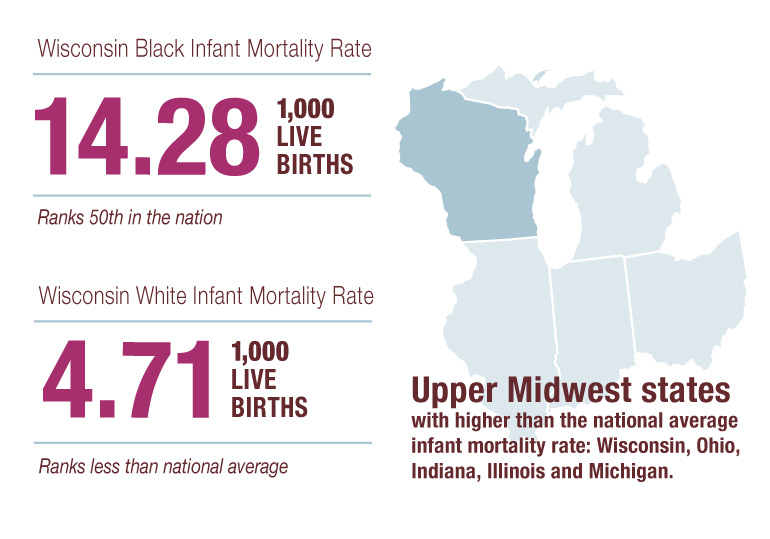

But Wisconsin’s disturbingly high rate of black infant mortality—over three times the rate of white infant mortality here—returned by the late-2000s and has remained elevated.

Rather than listen to people talk about or study the issue, Murray wanted to make a difference. Today, she and fellow doulas, along with physicians, medical professionals and community advocates—many of whom are African-American women—are part of an emerging grassroots movement in Madison to turn the black infant mortality rate around.

Murray’s degree in community sociology from UW-Madison and her training as a doula gave her skills to take her advocacy efforts to a new level. She wanted to bring back what she knew worked, so she and fellow doula Tamara Thompson co-founded Harambee Village in 2014.

Modeled off of Harambee Center, the new project focuses specifically on maternal health and birth outcomes. The organization offers community-based doula services, breastfeeding support and a variety of parent support services. It serves primarily Black women of lower income and focuses on reaching out to marginalized populations. It’s also training more doulas of color to reflect the population they serve.

Solving the problem will likely take some time, but Murray and other advocates are committed in the face of the egregious facts. Wisconsin is worst in the nation for infant mortality among African-Americans, with 14.28 deaths for every 1,000 live births. Black mothers are also more than three times as likely to die during or after pregnancy or childbirth compared to their white counterparts.

Changing these statistics is currently the No. 1 health priority of the Dane County Health Council, which includes all four major area health care providers, along with the Public Health department, United Way, Madison Metropolitan School District and other stakeholders.

At all levels, black women, those most directly impacted, are taking the lead in improving their birth outcomes.

LACK OF GOOD FAITH

None of the mothers interviewed for this story had heard of a doula before they were connected to Harambee Village. Doulas provide nonmedical birth support, accompanying the mother throughout the labor, attending to her physical and emotional comfort, while helping her make informed decisions. Doulas will often discuss a birth plan, or expressed wishes for the birth such as use or avoidance of pain medication, with their clients.

Diamond Clay had three main preferences for her birth at a local hospital: She did not want to be treated by students, she did not want an epidural and she wanted skin-to-skin contact with her baby immediately upon birth. Despite stating these both verbally and in writing to her care providers, Clay did not get any of these preferences. Many women change their mind about getting an epidural in the pain of labor, as did Clay. But despite her clear request, twice students attempted procedures— including the epidural—and had difficulty, requiring a full doctor to step in.

When the labor stimulant Pitocin caused the baby’s heart rate to drop, the doctors decided to do a C-section. As she walked down to where they would perform the non-emergency surgery, Clay was asked if she had regained feeling in her legs and she said yes, indicating the need for additional anesthetic. But she was not given any before doctors began to cut. As her partner filmed the birth, Clay screamed in pain. She was then given more pain medication to the point of being unconscious by the time her baby—a girl—was out and could be held, so she did not get the skin-to-skin contact she wanted. Months later she’s still having nightmares from the experience.

Murray, who served as Clay’s doula, has helped her process and recover from the traumatic birth. “She checked in with me every day,” Clay says of Murray’s postpartum support. “Just that simple, ‘How are you doing?’ or, ‘Do you need anything?’ really made an impact on my life afterward because I still felt like it’s not over, like I can still make a positive outcome of what I just experienced,” Clay says.

REFLECTING THE POPULATION SERVED

Harambee Village, housed within the East Madison Community Center, complements the center’s other programming, including the Today Not Tomorrow Family Resource Center, which offers parenting support and community baby showers.

Just being in a space with other black women for mother-baby groups or breastfeeding support was comforting to Anglinia Washington, a client of Murray’s who’s attended Harambee Village events. At other local offerings for pregnancy and young motherhood, she was always a minority. “You go to the classes and stuff and we’re the only black people there,” she says.

Washington, a finance officer with the Wisconsin Legislative Council, found out about Harambee Village through a friend. As a first-time mom with some health risk factors, she was grateful to have Murray’s support as her doula. She needed to be induced and had some concerns about Pitocin, but Murray explained her options every step of the way. In a birth she describes as “awesome” she was able to labor in a tub and listen to Michael Jackson until the baby was ready to be pushed out. Now 6-month-old baby Ella reflects her mother’s calm, happy demeanor.

Washington’s health insurance covered a portion of the doula fee. The rest was covered through a scholarship, which Harambee Village funds with grants and revenue from privately-paying clients. Most private-practice doulas charge fees of $1,000 or more and insurance companies rarely cover the service. “There’s a lack of diversity and a lack of access to [doula] services so a community-based agency focuses on providing access to all birthing people,” Murray says of Harambee Village. “We’re doing that by training people from the communities that we’re serving so that we are reflecting the populations that we serve, because we know that works best.”

FROM BEAUTY TO TRAGEDY

In September 2016, Cassandra Burrell was nine months pregnant and staying in a shelter, new to Wisconsin with no friends or family nearby when her social worker connected her to doula Tamara Thompson. When Burrell went into labor Thompson met her at a Waukesha hospital. “She lit candles, she said a prayer, she held my hand through the whole birth. She was there, and it was so beautiful, and I was so blessed to have her,” Burrell says. “There’s a lot of women like me that never had somebody to hold their hand and let them know that it’s going to be OK and be there to be an advocate just in case any complications go wrong.”

Sadly, Burrell’s son, Derrick, died just four days after birth. He was full term and a healthy weight, so his sudden death was a shock. Thompson was there for Burrell through the grief and they remain close today. “What happened to me was very tragic, but she always uplifted me every day, always came to check up on me…Just to have that type of person in my life means the world to me,” Burrell says.

BEING INCLUDED

Having served as doula for both black and white clients, Murray says she’s witnessed a disparity in medical treatment between the two. While white mothers are given options, black mothers tend to be given directives, she says. Washington experienced this when her newborn’s bilirubin level was high—which can lead to jaundice—and a nurse pushed formula, even though Washington was trying to breastfeed. Breastfeeding is known to improve health outcomes for both babies and mothers.

“A lot of times I’m not given options,” Washington says. “Like with the nurse in the hospital, it was ‘Oh, we have to give her formula. This is what we have to do.’” A different nurse the next day said that rather than being given formula for her baby, Washington could have been given a breast pump to get her milk to come in faster.

Clay also wanted to be more included in her health care decisions. “I was more comfortable with what Tia (Murray) was saying because she gave me options and the doctors didn’t give me options. They just said, ‘This is what you have to do,’” she says. After her daughter, Valani, developed jaundice and needed to be treated in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Clay decided to transfer care to a different hospital. There she had a better experience, where she says, “We made decisions together as if I was working there with them. And I felt like I was a part of their team, they were not leaving me out of any information that I needed to know.”

Micaela Berry, another doula with Harambee Village, has been doing birth support work since she was a teenager watching her mother give birth to her younger siblings.

She, also, has witnessed differences in how her white clients and black clients are treated. “My clients go through things that you hear from 1960s, ’70s, but to see them in the 2000s is really disheartening. I’ve had clients of color who were not encouraged to breastfeed, who were automatically given formula to take home, and these were women who had expressed—as I had expressed—that they would like to breastfeed,” Berry says.

Nationally, black women breastfeed at lower rates and for shorter duration than their white and Hispanic counterparts, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This may lead to assumptions by medical staff that then prevent black women from getting the breastfeeding support they desire. “They brought the breast pump in, but they never told me how to use it. I spent seven days in the hospital and on my sixth day is when they taught me how to use the breast pump,” Clay says.

The African-American Breastfeeding Alliance of Dane County is working to change the disparities by offering breastfeeding consultation and education to black families.

MORE THAN A STATISTIC

Dr. Jasmine Zapata is a pediatrician and preventive medicine doctor with UW Health. This spring she and Dr. Sheryl L. Coley published a paper in Women’s Health Issues, demonstrating a discrepancy in what patients of color and care providers perceive as quality of prenatal care. The patients interviewed were all black or biracial mothers who had given birth at a hospital in Dane County in the previous six months. All but two of the care providers interviewed were white. While both groups valued timely scheduling and appropriate screening, the patients saw much greater need for cultural sensitivity, compared to the white care providers. The study notes one mother as saying, “For them, they know what statistics tell them. You know what I mean? It’s, we’re numbers and not people.”

Berry also characterizes the treatment some of her clients have received as dehumanizing. “It just seems that there’s times where women of color are not even deemed people, they’re just another birthing object, almost. And that’s hard for me, it’s really difficult, especially because you want to be able to enjoy that magical birth no matter what the circumstances… To sometimes get situations where you have to go into defense mode and advocacy mode takes away from that,” Berry says.

DIRECT FROM THE SOURCE

Lisa Peyton-Caire is helping lead an effort to hear directly from the people behind the statistics—those who have experienced black infant mortality. Peyton-Caire’s Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness and Annette Miller’s EQT by Design, LLC are coordinating a series of community engagement sessions with mothers and their close family members who have had a low birth weight baby or have lost an infant. Low birth weight, usually a result of prematurity, is one of the main causes of infant mortality.

The goal of the project, termed “Saving Our Babies,” is to reach at least 200 people this summer and fall to gather perspectives on the greatest factors in black mothers’ wellbeing, including access to and quality of health care, access to healthy food and financial stability. The project was commissioned by the Dane County Health Council and will result in a report that can inform next steps in addressing the issue.

GIVING BACK

Despite her harrowing birth experience Diamond Clay was so impressed with the advocacy and support of her doula, Tia Murray, throughout the process, that she is now training to be a doula with Harambee Village herself. She is studying books on birth and will take a three-day training course before a test that, once passed, will earn her certification as a doula and breastfeeding consultant. Clay is also currently working as Murray’s executive assistant and has just been accepted into the UW-Madison Odyssey Project, which helps adults with economic challenges access college. She plans to earn a bachelor’s degree in social work. In the meantime, she wants to give back to other moms navigating birth for the first time. “I want to become a doula because I want other women to not have to experience this and to help them advocate for themselves, like I wanted to be able to do for myself,” says Clay.

For more on the causes of this disparity, click here.

Read about one doctor’s work on this issue here.

Read more about what UW Health is doing to address this issue.

Comments are closed.