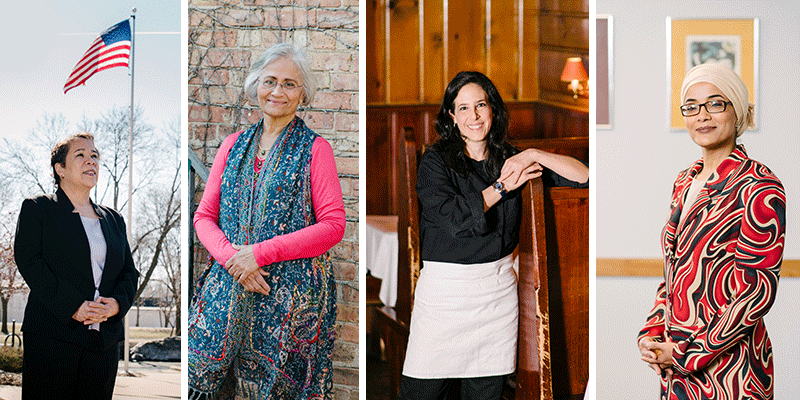

By Megan Roessler | Photographed by Hillary Schave

Immigrants have always had a hand in shaping American culture and society. The diversity of passions, ambitions, customs and perspectives that they bring to Madison and beyond create the storied American melting pot. In distinct and meaningful ways, immigrants help communities to thrive. Yet, those positives can sometimes be lost amid today’s negative political rhetoric.

Four Madisonians from diverse backgrounds—Colombian, Indian, Sudanese and Mexican—are among those who have become steeped in the American way, while retaining and sharing the rich cultural fabrics of their countries of origin.

Three parts make a whole: Natalia Chehade

Natalia Chehade’s parents each emigrated from Lebanon to Cali, Colombia, where they met. Growing up, Chehade was immersed in these two cultures. On Cali’s palm tree-lined streets, vendors sold chontaduro, or peach palm fruit, a salty, bright red fruit served in a little plastic bag, and neighbors offered to fix purses and appliances. At home, the language, dress, music and most significantly, the food, were all Lebanese. “Food was there, 24/7,” Chehade says. “At breakfast you talk about what you’re having for lunch. At lunch it’s what you’re having for dinner tomorrow.” In part, it’s this environment that prompted her to become a pastry chef. If you’ve been to the Tornado Steak House, or its sister restaurants Tempest or The Weary Traveler and had room for dessert, chances are it was made by Chehade.

Chehade has been the pastry chef at the Tornado Steak House for the last five years and at The Weary Traveler for the last 10. She won third place in the “Favorite Local Pastry Chef” category of Madison Magazine’s “Best of Madison” polls in 2018 and 2019. Additionally, she has opened a catering company—Savour Desserts and Catering. When opening Savour, she carefully deliberated the name, not wanting people to assume she only cooked Colombian food. The blending of cultural identities is something Chehade is familiar with, and when she cooks for her friends, she makes Latin food with a Middle Eastern twist.

After attending culinary school in Madison, she and her husband moved to Puerto Rico in 2000. Both of their sons were born in San Juan. In 2009, they returned to Madison. At home, they speak Spanish—it’s important to her to celebrate their family heritage and instill this in her children, taking them on trips to Puerto Rico and Colombia. “It’s their culture,” she explains. As for herself, she says, “Sometimes it takes a while to belong, and to catch up.” There’s a homesickness and a struggle to reconcile these international roots and communities. “I’m proud to be who I am. Latina, Middle Eastern, American.”

It comes as no surprise that her face lights up when she talks about Cali, the way that someone can only feel about their hometown. But San Juan and Madison are her homes as well, and Chehade has truly made a name for herself in Madison’s thriving culinary scene. Each place and each culture is part of her identity. Someday, she says she’d like to go to Lebanon. Because after all, it’s part of who she is.

Of the Same Universe: Lalita Sankaran

“I feel like my life started after 50,” Lalita Sankaran declares. She makes a strong case. Sankaran, who went back to school at 46, worked as an occupational therapist at some of Madison’s prominent hospitals and, after retiring, volunteered as an exercise instructor at the Fitchburg Senior Center.

And she isn’t done yet. Currently, she’s working with her daughters to open a wellness center at the Garver Feed Mill on Madison’s East Side: Kosa Ayurvedic Spa and Retreat.

The wellness practices and services at Kosa (pronounced kosh-ah) will draw heavily from those that Sankaran grew up with in Mumbai, India. She explains that this is called Ayurveda, a combination of the words ayur meaning “life” and veda meaning “wisdom”.

The main idea? “Draw people into their own bodies, and treat them from the inside out.” While Kosa isn’t a café, it will include food as an integral part of healing and the spa experience—much of it made using Sankaran’s own recipes. In her home kitchen, she has 40 jars of spices, all used in different combinations to create complex, flavorful dishes that she shares with her children and grandchildren.

Sankaran calls up a photo on her phone; she and two of her six grandchildren smile at the Indian celebration of spring, Holi, that her family organized at the children’s school. Sankaran explains, “Being an immigrant has meant many things to our family. While integrating and learning many of the Western values and traditions, it also means sharing and inviting the community to participate in learning about India and various other cultures from around the world.” To her, this means hosting Thanksgiving and Christmas, in addition to celebrating and sharing the holidays that she grew up with, like Holi and Diwali.

One of the qualities Sankaran takes pride in is her resilience. She believes she learned much of it from her mother. After Pakistan split from India in 1947, when Sankaran was just months old, her family moved to Mumbai—then called Bombay. Completely uprooted, her parents built their lives from the ground up. Describing life in a bustling city, she says, “My friends were Muslim, Hindu, Jewish…” They all attended a Catholic school. This unity across differences is a theme that arose again in her life. When Sankaran and her husband moved to Boise, Idaho, in 1974, she was homesick. One day at the public library, a woman noticed her sari and greeted Sankaran with a “Namaste.” They started chatting in Hindi, and the woman, Lois, became what Sankaran considered her ‘adopted Mom’. Both stories prove one of Sankaran’s beliefs. “I believe that, being born into different cultures doesn’t really matter,” she says, “because deep down we are all part of the same universe.”

A duality of cultures: Rihab Taha

Rihab Taha loves the idea of little free libraries. It’s fitting, on one level, because she’s an avid hiker and reader. At another, it’s because Taha has worked for Doctors Without Borders and currently helps refugees get settled in the United States through her job at Jewish Social Services. Charity is in her nature, and it goes a long way.

Taha grew up in Sudan, raised by an Egyptian mother and Sudanese father. She’s traveled extensively—in high school, she earned a scholarship to study Russian in what was then the Soviet Union. Later, in 1991, she studied medicine in Cairo to become a pediatrician.

After this, she joined Doctors Without Borders, an independent global medical response agency that currently operates in 60 countries, often amid hostilities. “It took a long time to convince my dad it would be safe,” she says. In fact, there were times when trips were cut short because they were too dangerous, but still, Taha enjoyed this job.

After working in Saudia Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and thinking of educational opportunities for herself and for her children, she decided to come to the United States. “If someone is in a good situation or a safe situation…It isn’t an easy decision to leave,” she says.

Taha’s plan initially had been to stay for three to five years, and she remembers the moment she first arrived: “May 10, 2000, 7:25 p.m.” Her oldest daughter was born later that summer, and each year they celebrate together. She discusses the nuances of raising three first-generation American children, noting that they are more direct than she is. Together they joke that after 19 years of living in the United States, Taha still hesitates to ask things of the people around her. There’s a duality of cultures in Taha’s life, and it’s one that is especially relevant in her work.

“I’m an African Muslim woman who works at a Jewish organization,” she explains, smiling. “You can see the curiosity on people’s faces.” While her current position in refugee resettlement seems— and in many ways is—a big change from medicine, when she saw the job posting, Taha knew she was a perfect fit. Recalling how she felt when she first moved to Madison, she describes it as a challenging time. “I was the only Arabic-speaking person.” There are many details of everyday life that she became more aware of: “learning a different language, learning a different culture, different weather.” Taha wanted to use this experience to help people in similar situations, because as she says, “I was in their shoes.”

For her, that’s what it’s all about—not the money, or the prestige, but the number of people she can make smile. Taha’s charity and empathy are clear, and she says that it’s important for people to understand different perspectives on the same issue by listening, caring and learning.

Doing Her Part: Elena Jimenez-Quiroz

Elena Jimenez-Quiroz describes being a Community Impact Coordinator at United Way as her best job. “It let me use my strengths,” she says. There, she could be focused and organized, but also take the values of generosity and hard work that she grew up with and put them into action. She retired in March after 16 years with the United Way, but she plans to continue paying it forward.

One of her first projects when working on United Way’s Community Impact team was working with the Latino Advisory Delegation. “It was very inspiring to see Latino leaders come together from across the community,” she says. Representatives came from the University of Wisconsin and Centro Hispano, and included youth delegates, among others. Together, the representatives worked to address specific issues affecting the Latino community.

Another project she speaks highly of is Seasons of Caring— an annual program where she led several families of volunteers in short-term projects, sharing the spirit of generosity instilled in her with younger generations. “My heart is for parents to give attention to the children, play with them and give them good values and education to have a good future,” she says. “That’s why I will still be a volunteer wherever I can help Latino families.”

Jimenez-Quiroz grew up in a big family in Quéretaro, Mexico, in the central part of the country. She was brought up with a foundation of strong values for hard work, respect and honesty, which she maintains to this day. “I have a lot of respect for craftspeople in Mexico,” she says, and describes the handkerchiefs stitched and sold by indigenous Otomi women in Quéretaro that she grew up appreciating.

She came to the United States in 1984 to have better opportunities. She’s grateful for the friends and families she found, too. “I don’t get bored,” she says, smiling. Jimenez-Quiroz describes herself as an environmentalist and says that the lakes are among her favorite parts of Madison, especially given their contrast to the semi-arid climate where she grew up. There, she explains, cactuses grew everywhere.

Jimenez-Quiroz takes pride in being part of Madison’s community. Now that she’s retired, she looks forward to taking art classes and volunteering. Although there are people struggling here, she says that there are also people who care—from the small nonprofits helping people less fortunate, to those working to get funding for medical research, to climate change activists. She continues to do her part to make the city a better place for all.

Comments are closed.