STRUGGLING WITH DANE COUNTY’S HEROIN ADDICTION

When the Wisconsin Department of Health Services reported that more people died from opioid overdose than car accidents in 2015, it was as if someone had shaken state lawmakers awake. An opioid task force was formed and legislation swiftly passed under what’s called the HOPE, or Heroin Opiate Prevention and Education, agenda.

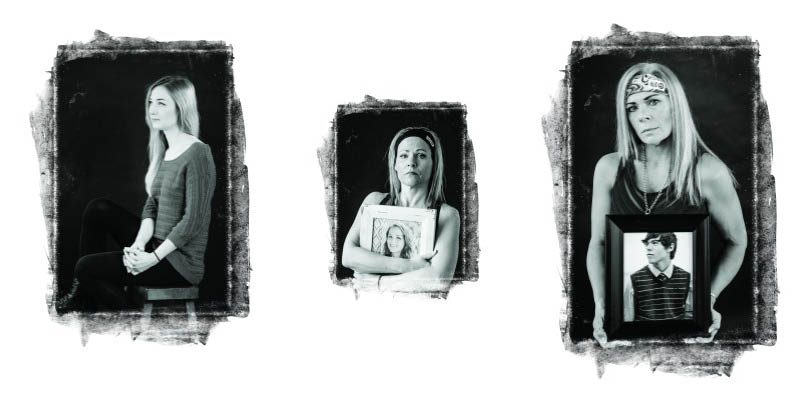

The increase in addicts and, tragically, fatal victims of opioid abuse, prompts the question: Who are these people using opioids, including heroin, in our communities? Isn’t heroin an inner-city drug?

The reality is that it’s people like Cody Sesolak and Hillary Roe, both from Waunakee. Both were in their early 20s and from middle-class families. They were athletic and good students. Both died from heroin overdose, alone in their bedrooms at their parents’ homes.

It’s people like Veronica and Alison, who requested that BRAVA not use their last names as they try to put their heroin use behind them. Both are from Madison, are in their 20s and had stable childhoods. Both were introduced to prescription painkillers in their teens, then in the blink of an eye, were shooting heroin and watching the bottom drop out of their lives before finally seeking treatment.

These are the most-at-risk faces of opioid use today in America: Young, white, middle-to-upper class men and women. According to the CDC, in the past decade heroin use has more than doubled among young adults ages 18-25, particularly nonhispanic white individuals. From 2010 to 2014, among the general population heroin overdose deaths have increased: 267% among the white population, 213% among the black population, and 137% in the Hispanic or Latino population. Heroin strikes at all economic classes.

Many in the law enforcement and medical community trace the rise in heroin use to the increase in prescription painkiller use. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that approximately three out of four new heroin users start with prescription opioids such as OxyContin, morphine or Percocet. Dr. John Ewing, co-director of UnityPoint Health-Meriter’s NewStart addiction services program explains that in the 1990s when OxyContin became widely used, pain management research was often funded by pharmaceutical companies. Pain became the fifth vital sign, and the focus became managing and getting rid of pain to improve patient satisfaction.

“Doctors were taught to prescribe opiates for pain, and doctors and patients were told that OxyContin was not addictive,” he says. “On the street, people were crushing it and snorting it, or shooting it, so the maker of OxyContin was forced to change the formula to make it harder to crush. The street value dropped and people switched to heroin in droves.”

Alison, a self-described nerd in high school who suffered from anxiety, says that when she was invited to a party at age 16, she immediately turned to marijuana and alcohol to feel close to the kids who never paid attention to her before. She dabbled in over-the-counter medication for a light high, and was offered OxyContin not long after.

“I remember the first time I did an opiate. It took away everything that felt wrong inside of me and it didn’t take long for me to try heroin after that,” she says. “Heroin should be this scary, horrible thing, but everyone I was around at school was trying it.”

In 2011, she left for college, her lifelong dream, and found she could afford her habit of snorting heroin, and she still earned straight A’s. Even a near-death overdose, where she had to be shocked back to life, didn’t scare her straight. She wasn’t ready to quit. Crying and alone in her bedroom, she taught herself to shoot heroin two days after graduating college.

“The second it hit me, I knew this was the end,” she says. “I hated myself so much for what I was doing that I couldn’t bear to look at any of my friends. I didn’t want them to see the mistakes and the person I was turning into.”

Veronica found herself alone as well in the height of her drug use, living in her car to escape “very bad people,” she says. She describes her childhood as sheltered, but still she was filled with anxiety and was bullied. When she graduated high school, she turned to drugs and alcohol, which helped her feel loved and close to others for the first time in her life.

Then everything changed when she was prescribed OxyContin after a root canal in her early 20s.

“It just made me feel so relaxed. I told my doctor that I had pain when I didn’t. He kept prescribing it over and over,” she says of her introduction to the opiate. She eventually moved to Percocet and became a dealer to support her habit. She was introduced to heroin and eventually crack cocaine. Suicidal and depressed, she quit her job and began living in her car to escape the people that controlled her life. A private investigator hired by her mother found her a week before she was to be trafficked to Costa Rica.

Veronica’s addiction led to some harrowing, often criminal experiences. She was held at gunpoint during a drug deal, was arrested after a 120 mph police chase, and often stole from those she cared for. Susan Gonzalez, a detective with the Dane County Narcotics Task Force, says the crime associated with opioid abuse is the most noticeable effect on our community.

“Some people will spend $50 up to $200 a day on heroin,” she says. “Where do you get that money if you don’t have a job? Burglaries, bank robberies, and often this leads to shootings and homicides.”

Gonzalez’s focus is on heroin cases, but the Task Force’s primary responsibility is getting mid- to upper-level drug dealers off the streets, such as the dealer Gonzalez recently helped convict and who was sentenced to eight years in prison.

She adds that not only is heroin coming from larger cities in greater amounts, but fentanyl—a synthetic opioid that is often prescribed for advanced cancer pain, but now is found on the street—is often mixed with heroin to increase its potency.

“As a result, we see a lot of overdoses due to the users not knowing the potency of the heroin, or the supplier changes the mixture and the dealer doesn’t realize it,” explains Gonzalez.

According to a 2016 Wisconsin Department of Health Services report, from 2006 to 2015 the rate of heroin overdose deaths increased 880 percent across the state, a staggering statistic that has nearly crippled the ability of facilities to treat the victims, and spurred a collaborative effort from agencies across the state to curb the epidemic.

Dr. Randy Brown, associate professor with the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, and the director of the Center for Addictive Disorders at UW Hospital, says that having a variety of programs available to keep an addict safe is critical in bridging the gap between being ready for treatment and receiving treatment, which often takes two weeks or more from first contact.

One of those stop gaps is Naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of opioids such as slowed breathing or loss of consciousness, and is used to prevent overdose deaths. Widely available at pharmacies, the drug was also part of the original seven bills passed in 2014 that laid the foundation for the HOPE agenda. Now, all levels of EMTs, first responders, police and fire personnel are eligible for training on how to administer Naloxone.

Beth Menke, communicable disease outreach specialist with Dane County Public Health’s Needle Exchange Program, explains that such programs have the same focus on harm reduction as Naloxone. If an addict isn’t ready for treatment, “you meet them where they are, not where you want them to be,” Menke says. “One thing that people are not aware of is the amount of shame that is attached to being an addict. It keeps people from talking to their doctor, or coming to a needle exchange.”

The two needle exchange locations in Madison give out 45,000-50,000 syringes each year and while it may seem like this encourages drug use, Menke notes that the primary focus of exchanging needles is disease prevention. Free Hepatitis C, AIDS and sexually transmitted infection tests are available at each location.

In March 2017, the state legislature’s budget committee approved funding for an additional 17 bills aimed at combatting the opioid epidemic, including additional funding for treatment and diversion, or TAD, programs that give nonviolent offenders treatment options after their initial court appearance instead of jail time, giving law enforcement and judges more options to prevent recidivism.

Addicts often don’t admit they’re ready for treatment until the lowest point in their lives. For Alison, it was when she found herself laying on a cement bed in a Dane County jail, just three weeks after graduating from college.

“That day is when I finally realized that I was not in control and I admitted I had a problem,” she says. But getting into treatment was difficult for Alison since neither she nor her parents had health insurance. Her mother called and begged county officials for assistance. Finally, Alison was admitted to a bed at Hope Haven, which led to further recovery treatment.

“I spent 10 weeks in treatment and that treatment got me into another recovery program. Finding my spot in [the recovery community] is what changed my life and what really got me serious about recovery,” Alison says. Still, she admits, a relapse got her kicked out of Oxford Sober Housing 90 days after leaving treatment.

Having a plan—a completely new life really—is key to success, says Brown of UW’s addictive disorders center.

“The average time that someone has been actively using before they get to treatment is close to 10 years, so you can imagine they’ve become pretty entrenched in their social network. Breaking out of that is a difficult job in recovery,” Brown says.

After three attempts at detoxification, Veronica also found success in a similar treatment path as Alison, and concurs that Sober Living treatment and other required meetings held her accountable, even through a relapse.

“I think I needed that relapse just so I could realize that I can never go back. This time around since I’d already gotten the help, I was able to be honest about it and ask for help,” she says.

Brown notes that relapse rates in the first two months of treatment exceed 90 percent without medications like Methadone or Suboxone, which can either allow an addict to function as the addiction is tapered, or at least prevent overdose death. He explains that an addict is at highest risk for overdose following a period of abstinence from an opioid, when tolerance is low but the same potency is used as before.

“It’s often studied in jail populations: The two weeks after release from jail, the risk for death is 129 times higher than at any other period in their lives,” he says.

While the battle wages on the streets, on wait lists for treatment, and on the floor of the state legislature, those who have suffered are focused on removing the stigma of addiction by telling their stories, and showing the true face of opioid addiction: The families of athletes and straight A students taken too soon. The teens who suffer with anxiety and carry the burden and shame of their addiction with them into adulthood. And those that eventually come out clean on the other side, ready to start again.